Make it Practical #3: Andrea Cornwall's "Women's Empowerment: What Works?"

It's all about the process

Before I get started, I just want to say thank you to those who have shared feedback and posted comments about my Make it Practical series. In my next post I plan to share some of your comments so please keep them coming!

I’m closing this three-part miniseries about the concept of “empowerment” with the paper Women’s Empowerment: What Works? by Andrea Cornwall (2016).1 I’ve read many briefs and papers about “what works” for women’s empowerment and this is one of my favorites. While many other papers and briefs focus on specific interventions like infrastructure or land titling, Cornwall highlights lessons about the process, which have more to do with how an intervention is designed and implemented than the intervention itself.

Cornwall’s focus on process is not only unique within the research I’ve encountered. It is also notable because one of the critical aspects of the original characterization of “empowerment” was that it was a socio-political process – not a single or even a set of interventions.

A note about methodology

Cornwall makes her argument by first framing it in the history of empowerment, which I discuss in my earlier two posts: how it began as a radical approach led by South Asian feminists to fundamentally change imbalances of power and was then co-opted and diluted by governments, NGOs and institutions as part of a broader macro trend toward market-driven solutions to political problems. She then draws on lessons from the Pathways of Women’s Empowerment Programme, a large program funded by the British, Norwegian and Swedish governments in the 2010s, which used an interdisciplinary approach to explore the various and complex ways in which women experience empowerment.

It’s all about the process

Cornwall highlights five programming processes that consistently show an impactful contribution to women’s empowerment. I’ll briefly go through these processes, then share my takeaways at the end. All of the quotes are from Cornwall’s paper, unless otherwise cited.

Process 1: Build critical consciousness

Critical consciousness is the process of expanding one’s own vision for oneself of what is possible for you to become and achieve - and to also become critically aware of the oppressive systems at the root of your subjugation. Remember that critical consciousness was one of the foundational aspects of empowerment (see Make it Practical #1), but also one of the elements that was sifted out when institutions tried to scale and fit empowerment into neoliberal frameworks (see Make it Practical #2). But its impact cannot be understated.

“Pathways researchers found again and again that where empowerment initiatives include a dimension to actively engage women in critical, conscious, reflection on their own circumstances and to share that process with other women – what Paulo Freire called conscientizaçãdo and what feminists might describe as ‘consciousness raising’ – there can be a marked enhancement of a programme or project’s transformative effects.”

Process 2: Engage “front-line intermediaries” as agents of change

Front-line intermediaries are the trainers, coaches, teachers, social workers, loan officers, health care workers, agro-dealers, and other people who work directly with the women and communities you are trying to impact – i.e., on the frontlines – need to have the knowledge, resources, and power to enable others to be empowered too. In other words, they must be ‘empowered’ themselves.

“The best of laws and policies and most beautifully designed programmes can falter and fail if those who deal with putting them into practice are not themselves engaged and empowered as agents of change…. empowering front-line workers and enabling them to grow in their own capacity to act as agents of change can significantly increase the effectiveness of interventions.”

Process 3: Build collective power between and among women (and women’s organizations)

Empowerment relies on building collective power to lead and influence change that will improve the situation for all members of the disempowered group.

“When women are able to come together and organize themselves to make demands, build constituencies and alliances, they are more likely both to succeed in making changes for other women and also experience for themselves the empowering effects of mobilization.”

It’s also worth noting that collective power often begins with the process of building critical consciousness that leads to a sense of collective solidarity (See process 1, above). Cornwall cites an example from the Indian sex workers’ collective VAMP:

“the first step was developing a critical consciousness of their situation, which allowed sex workers and their children to reclaim their dignity and sense of self-esteem and respect for themselves and each other. The second was the process of building… [skills for working together] collectively and creating relationships of solidarity within a community that had once been fractious and divided.”

Process 4: Foster strong and lasting relationships with and within women’s organizations and movements

The rigid measurement and results-driven focus in the development sector tends to prioritize outcomes over relationships. Yet Cornwall points out that relationships are essential to empowerment outcomes. She’s talking about relationships between what we often understand as the being “the implementer” and the participant, client, beneficiary, constituent, or whatever term your organization uses to describe the people you are trying to help or serve. Partnerships with women’s organizations and movements that have authentic and lasting relationships with the community are particularly critical for any intervention focused on empowerment.

“women’s organizations play a vital role in supporting women’s empowerment. A key dimension of this role are the relationships of trust, loyalty and love that often bind these organizations together and are part of the story of their effectiveness.”

In addition, relationships between and among women are essential for building and sustaining collective power.

“collectivization and movement-building may result in better wages, but before these material gains come the solace of solidarity, the courage in collectivity, the sociality of shared struggle.”

Process 5: Use popular culture to challenge stereotypical representations of women

The Pathways program on which Cornwall bases her analysis was interdisciplinary. It funded and researched approaches that drew on the social sciences, arts, and humanities to explore the pathways of women’s empowerment. In doing so, it documented the powerful role that popular culture can play in influencing women’s ‘pathways’ of empowerment by challenging stereotypes, especially regarding sexuality. And yet, she points out, mainstream development rarely approaches popular culture as a valid and credible force for change.

“Surprisingly, little attention has been given by mainstream development to the significance of representation, beyond engagement with the use of popular communications-from soap operas to songs to comics – in health promotion…When considering what works to support women’s empowerment, it is therefore important not to neglect the significance of the arena of cultural production.”

What can I do?

Many of you are reading this and thinking that the way foreign aid and philanthropy is set up makes many of these processes nearly impossible to implement. Here are my suggestions for how to work around or within the system to incorporate these design elements into your programming.

1. Build relationships with and fund women’s rights and feminist organizations in the countries and communities where you organization is working. Over the past decade we’ve seen more and more funding dedicated to gender equality and development, whether to pay for gender analyses, gender training, or specific program activities. Yet very little of this money is going to grassroots women’s organizations: a study from the Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) found that “99% of development aid and foundation grants still do not directly reach women’s rights and feminist organizations.”2

Those of us who have any influence over how this money is spent need to seek out ways to redistribute and allocate much more of it to support women’s rights organizations and those working at or with the “frontline intermediaries.” Foundations and organizations with flexibility in their funding models need to be funding women’s rights organizations with as few strings attached as possible - not just as grants for individual projects, but for operating, building, organizing and creating.

“treat [women’s rights] organizations as innovators not contractors, and acknowledg[e] that real change cannot be reduced to short-run project cycles and depends on solidarity, which can be jeopardized by practices such as competitive bidding.”

2. Keep the ‘critical’ in critical consciousness. Back in 2017, I was excited to see “critical consciousness” in the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s Conceptual Model for Women and Girl’s Empowerment. This was unique at the time. It also fit with the trend summarized in Make it Practical #2 about how social-liberalism has brought back elements of consciousness-raising that neoliberalism shunned. I’ve observed that it is increasingly common for women’s empowerment programs to include elements of exposing women (or other marginalized genders) to new “mindsets,” or ideas, visions, and representations of what they might be able to achieve and become.

However, this is only a part of critical consciousness. Critical consciousness is also about being able to think critically about the world around you, recognize the oppressive systems that socialized you – and will continue to socialize you – to devalue yourself and that construct the barriers to your progress. This is the “critical” part. It may seem - on the surface – to be pessimistic, focusing on the constraints, and not “solutions-oriented.” But as Cornwall and numerous others show, this critical consciousness is an essential part of the solution to social change.

3. Value and create space for artistic and creative expression. Mainstream professional spaces dominated by white-centered American, Canadian and other colonizer countries have a tendency to devalue artistic and creative expression. It shows up as the entertainment before the senior official meeting that happens before the ‘real’ work begins. But, Cornwall is telling us that there is a real need and space for artistic and cultural production in the development, humanitarian, and human rights sector. People who control budgets need to find ways to incorporate funding – with artistic freedom and without cultural appropriation – for art that challenge stereotypes and present new ideas and representations of gender. Organizations like the FRIDA Fund do an excellent job of integrating artistic expression into their reports and publications. Population Works Africa seamlessly incorporates art and literature into its Decolonizing Development e-learning program. We need more of this.

4. These lessons are not just for women. Cornwall’s article focused on women. But it’s important to remember that the South Asian feminists who began the movement for women’s empowerment built on liberation ideas and theories developed by and for other and additionally oppressed groups, like the Black power and liberation movement in the United States and workers’ rights movements in Brasil. Further, women are not the only group marginalized by gender inequality and patriarchy. Non-binary, transgender, intersex, and other gender marginalized groups are often left out of mainstream development efforts for women’s and girl’s empowerment, especially if they don’t identify or express themselves as women (or girls). In my opinion, these lessons are not just for addressing gender inequality gaps, they are relevant to any group that is systematically and structurally subordinated.

What do you think? Email me or post a comment!

Cynara’s Gender Training Platform has *five* upcoming training workshops scheduled for 2022. All trainings cost a fee. We are introducing new tiered pricing structure with discounted rates for early career professionals and folks from low/middle income countries without the backing of a big organization. Click on each training for details about prices.

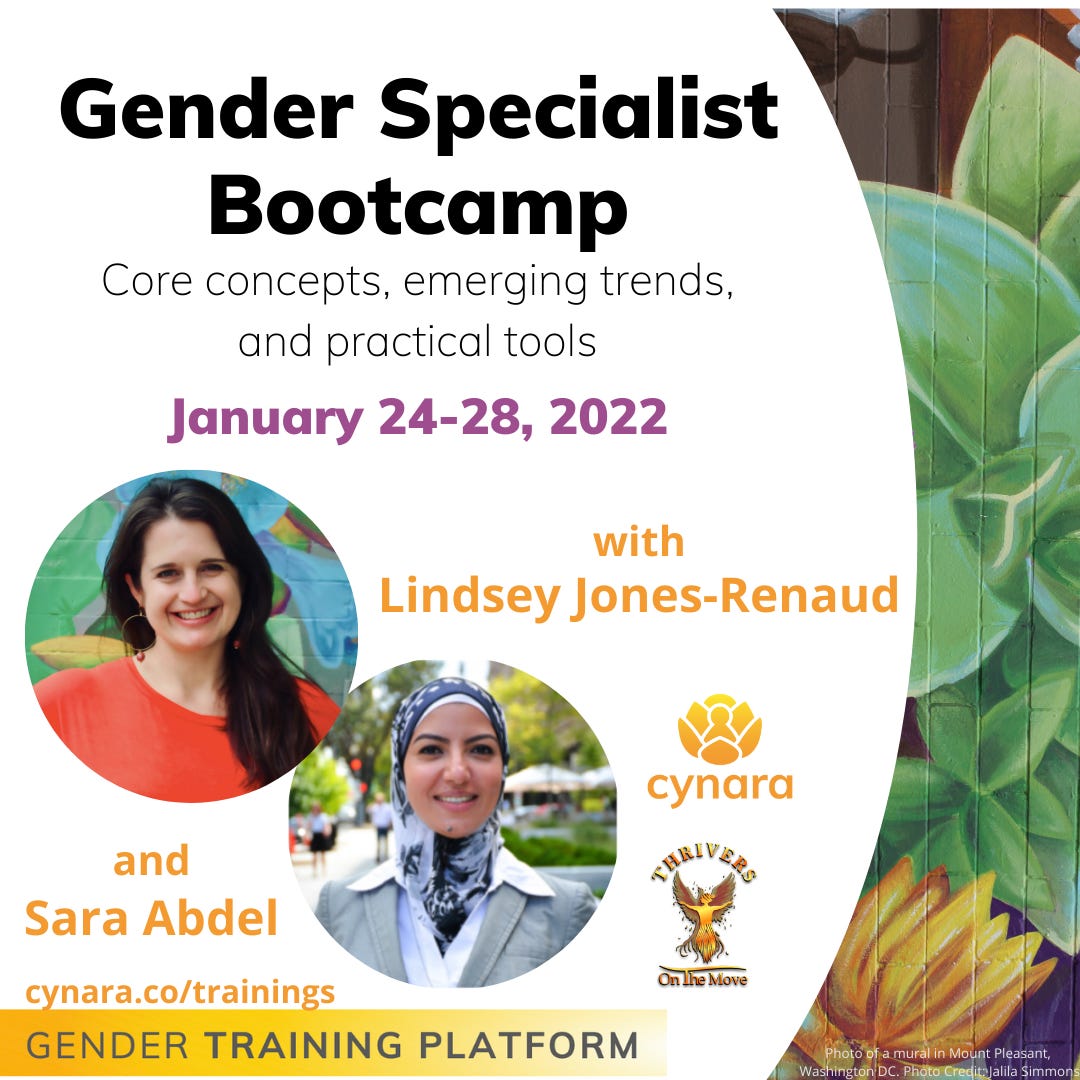

Gender Specialist Bootcamp: Core concepts, emerging trends, and practical tools

JANUARY 24 - 28, 2022 with Lindsey Jones-Renaud and Sara Afifi Afifi. LinkGender, Feminism, and Islam: Guidance for workers in the humanitarian and international development sector.

FEBRUARY 8-10, 2022 with Afaf Al-Khoshman. LinkHow to be a Gender Trainer: Facilitating transformative change through feminist pedagogies

TWO offerings (1) FEBRUARY 21-25, 2022 and (2) APRIL 4-8, 2022 with Lucy Ferguson. LinkDecolonizing M&E and Research: Practical guidance from a feminist approach

MARCH 29 - APRIL 1, 2022 with Michelle Lokot. Link

Cornwall, Andrea. “Women’s Empowerment: What Works?” Journal of International Development 28, no. 3 (March 28, 2016). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jid.3210.

Tenzin Dolker, “Where Is the Money for Feminist Organizing?” (AWID, 2021), https://www.awid.org/sites/default/files/awid_research_witm_brief_eng.pdf.